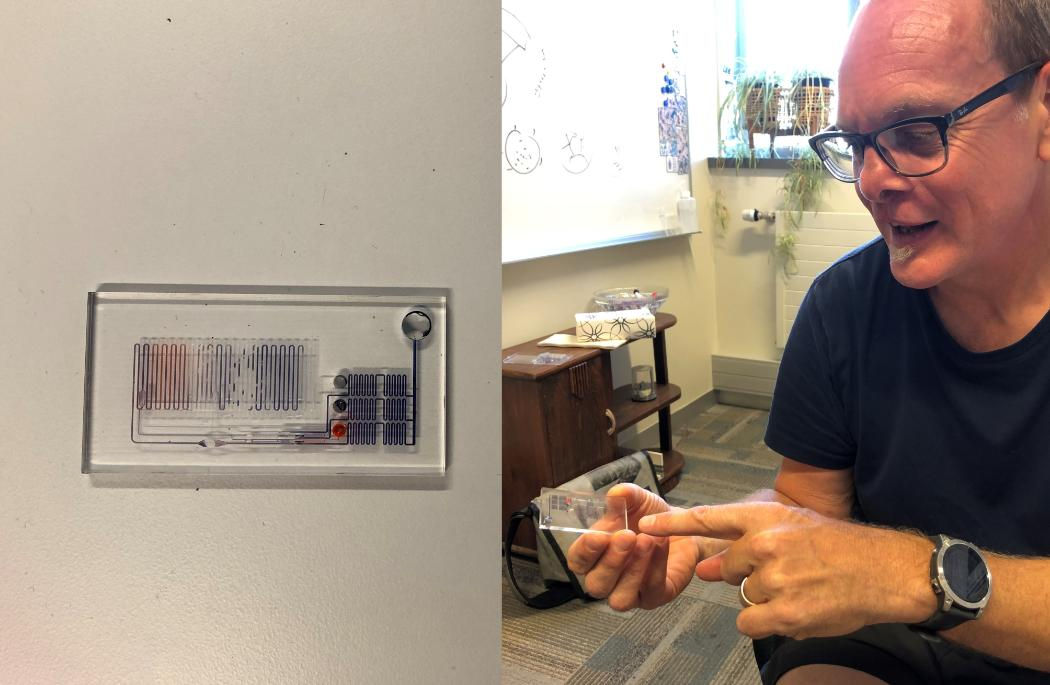

Professor Renwick Dobson with the portable "Lab-on-a-Chip" diagnostic device that can be used to analyse glucose levels in wine quickly and economically, enablng smaller wineries to do more testing.

Sedimental Factors

When you open a bottle of wine, sometimes you might find extra sediment at the bottom.

That could be precipitated calcium tartrate, a harmless crystalline solid made from two chemicals, calcium and tartaric acid, that naturally occur in grapes.

UC Associate Professor Ken Morison and PhD student Jack Muir received $166,047 of funding from the Bragato Research Institute to investigate factors that contribute to the formation of sediment in wine.

Precipitation in wine in a slow process, usually taking months. “You don’t know, when you’ve made a bottle of wine, when the customer opens it in six months’ time, whether there would be precipitate at the bottom or not,” said Morison.

While people in the past would decant the wine to remove the sediment, modern customers wanted perfect wine straight out of the bottle.

Recently, winegrowers have noticed that there were more occurrences of precipitate found in their wines, but they weren’t sure why. So they turned to UC for help.

Morison and Muir are creating a simulation that can be used to predict the likelihood of precipitation.

Precipitation is influenced by several factors, including the pH level, the presence of certain ions (atoms or molecules with an electric charge), and other things like sugars and alcohol.

Through initially analysing several varieties of wine from different areas, Morison and Muir will determine what typical compounds are found in wine and determine whether factors such as soil compositions and sprays employed by vineyards have any influence on the likelihood of precipitation.

All in a single chip

Fellow UC researchers Professor Renwick Dobson and Associate Professor Volker Nock also received funding of $65,000 from the Bragato Research Institute for his work on an affordable and portable diagnostic device that can measure the levels of various wine compounds, such as glucose.

Working with postdoctoral fellows Drs Julian Menges, Claude Meffan, and Azadeh Hashemi, and PhD student Daniel Mak, the team produced a plastic chip with neither moving parts or electronic elements that would measure glucose in a wine sample.

“The foundation of the project was a need in the diagnostic industry to have rapid tests that were really simple,” said Professor Dobson.

The device, which uses Lab-on-a-Chip technology, works due to a process called capillaric flow, which moved fluids through capillary action, akin to water being wicked by paper.

“One of the problems with capillary force devices is that their operations are tree like so if you’re going to do something that’s a complicated assay, in a diagnostic setting, you need to be able to stop [the movement of fluid] and start the flow again, mix things. These are much more difficult to do in a plastic chip with no moving parts or electronics.”

Drs Menges and Meffan developed a way to close off channels and prevent fluid movement in the chip, which allowed samples to be measured.

“We don’t make a lot of wine [in comparison to other wine producing countries],” said Professor Dobson.

“Our niche is that we do really good wine so to stay at the top of the market, there has to be a lot of testing. Almost every winery , big or small do various lab testing. A small winery might not have the equipment to do lab testing, so right now, they’d have to send it out to an external lab. It’s a cost to the producer. Each test costs around $25 and, for small wineries, it’s a significant cost and adds to their budget, especially during vintage.”

The diagnostic device would bypass that and still give wineries reasonably accurate results. “All they would need is to put the sample on the chip and it would tell you what the glucose levels are. It’s similar to a RAT (Rapid Antigen Test for COVID-19).”

The long-term hope of the team was that the chip could be used for medical diagnostics in the future.

For now, however, they’re sticking to perfecting their wine testing methods, expanding the tests to include diagnostics for malic acid, yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN), and alcohol.

PhD student Daniel Mak is also working on commercialising the chip under the name of Winealyse, which led to him being named a recipient of Kiwinet’s Emerging Innovator Programme award. The project also won UC’s 2021 Innovation Jumpstart Award in the Greatest Global Impact category, and Daniel was Research Runner Up in the 2022 Food, Fibre and Agritech Supernode Challenge, and Research Runner up in the 2022 Food, Fibre and Agritech Supernode Challenge.