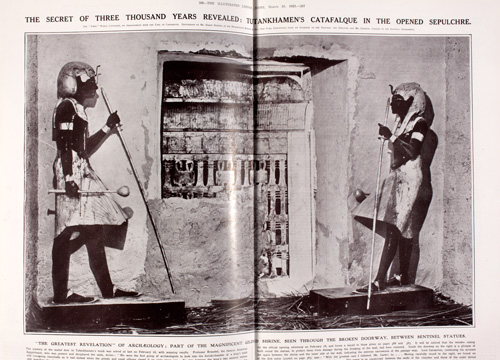

A desert valley on the River Nile’s west bank near ancient Thebes, known today as Luxor, is the site of many hidden underground chambers of pharaohs. Chosen as the burial place for most of Egypt’s New Kingdom rulers (1550-1070 BCE), in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens the tombs lie behind the site of the royal mortuary temples and beneath a pyramid-like natural mountain known as al-Qurn.

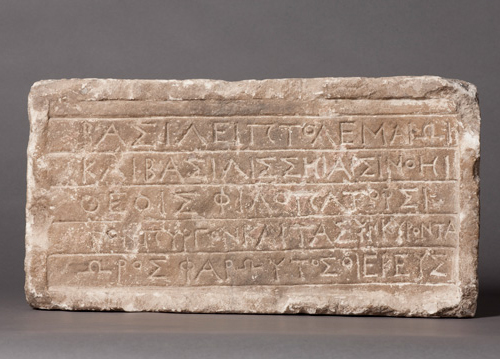

Following Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition to Egypt in 1798, many European adventurers visited the region. Detailed maps and drawings of the pyramids, sphinx, and Valley of the Kings at Thebes were published, leading to ‘Egyptomania’ - a rivalry between European nations to acquire artefacts. This culminated in a race to build up Egyptian collections in museums around the world, where many Egyptian treasures are still held.]